Manly male sports fans for a safer planet

A new study identifies "precarious manhood" as a barrier to climate action.

“(Be a man) We must be swift as the coursing river

(Be a man) With all the force of a great typhoon

(Be a man) With all the strength of a raging fire” — “Mulan” (1998)

Does caring about the climate make you feminine?

In some ways it’s a silly question. But in others, it’s a crucial quandary for those of us engaged in the climate fight. Because the sad fact is, lots of men avoid getting involved because they’re convinced it will undermine their manliness.

At least according to a new study.

The peer-reviewed paper is relatively straightforward. UC Riverside business school professor Michael P. Haselhuhn recruited participants for a variety of surveys and also examined existing survey data. He controlled for age and political ideology, which can affect how people feel about the climate crisis. And he consistently found a clear relationship between gender expression and climate concern.

Specifically, men who place a higher importance on “being a man” are less likely to worry about global warming, less likely to feel personal responsibility for reducing warming and less likely to think warming is caused by humans. Men who feel more anxiety over situations that threaten their masculinity — like losing at sports — are less convinced that climate change is affecting the planet as a whole (and the United States specifically).

Why do men — or at least, some men — worry that climate consciousness will dilute their hard-earned manliness? Haselhuhn found that the challenge arises among men who perceive “warmth” as a feminine trait. The problem being that caring about the environment is also seen as a warm trait, at least traditionally.

“It’s not just that men want to appear like men,” Haselhuhn told me. “They want to avoid looking feminine.”

In some ways, this is all intuitive and unsurprising: Lots of men have fragile egos lurking beneath their brash, bulky exteriors. I’m guessing Haselhuhn’s study was no shock to journalist Amy Westervelt and the team behind the Carbon Bros podcast, a fascinating deep dive into toxic masculinity and climate denial. Just think about Joe Rogan, who spews climate denial on the regular.

But Haselhuhn’s study stood out to me.

For one thing, it pinpointed a psychological mechanism that leads men — or at least certain men — to reject climate concern. So what if anything can we do to counteract that mechanism? If some men fear that engaging on climate might make them appear too warm, and hence too feminine, can we reframe climate action in ways that are less threatening to those men?

Unfortunately, Haselhuhn didn’t have a good answer. He told me that in his research, he’s tried reframing climate to make it about protecting your children, protecting your family. But it hasn’t made much of a difference.

“Maybe it ticks the needle a little bit, but it’s not the answer,” he said.

He did find in another study that if you ask men to forgive coworkers for workplace mistakes, they’ll often say no. But if you give men a chance to affirm their masculinity first — i.e. let them tell stories that prove how manly they are — and then ask them to forgive, they’re more likely to assent.

Alas, “that’s not so helpful in the real world,” Haselhuhn acknowledged. “You can’t go around puffing men up all the time and then ask them about climate.”

His study also caught my attention because it got me thinking about sports. Writing about sports and climate the last few years, I’ve sometimes wondered: Is there so little climate activism in U.S. sports because the industry is so male-dominated?

To be clear, I’m aware that women’s sports are growing rapidly in popularity, and that men’s sports have lots of dedicated female fans. But in the U.S., two-thirds of avid fans are men. The world’s 100 highest-paid athletes are men. The 50 most valuable teams are men’s teams. The sports economy is still predominantly male.

Which is unfortunate, because I’ve had trouble finding many examples of players in the Big Four U.S. men’s leagues — MLB, NBA, NFL and NHL — speaking out about climate. Surely some of them are simply avoiding politics. But is that the only reason? Are some of them afraid of looking feminine, to fans or to their teammates?

I reached out to Lew Blaustein, founder and CEO of the nonprofit EcoAthletes, which works with athletes around the world to promote climate action and sustainability. He told me 77% of the group’s 246 EcoAthletes Champions are women.

“While these women are truly inspirational/incredible, we are very well aware of the need for there to be more male athletes who lead on climate,” he said in an email.

I also talked with Allen Hershkowitz, a scientist who co-founded the Green Sports Alliance and now works with teams and leagues to limit climate emissions from their operations. He told me the vast majority of the team and league officials in charge of sustainability operations are women.

“I’d say 7 out of the 10 people I work with on climate and sustainability are women,” he said.

Like Blaustein, he wasn’t surprised by the results of Haselhuhn’s study. After noting that climate change hits women harder than men — and that men are more likely to work in the fossil fuel industry — he made the interesting observation that he rarely sees photos of female ICE agents. He believe’s there’s an empathy gap.

“I like to remind people that what we’re doing helps to alleviate human suffering. I just think women get it,” he said.

In my own reporting, meanwhile, I’ve found that it’s women leading the fight to use the immense cultural power of sports to oppose fossil fuel propaganda.

More than 130 female soccer players called on FIFA to end a sponsor deal with Saudi Aramco. The campaign to press the Dodgers to cut ties with oil company Phillips 66 was started by three women. The only California lawmaker to endorse the Phillips 66 campaign was State Senator Lena Gonzalez. The “Ted Lasso” episode where the team does, in fact, shun an oil industry sponsor was written by Ashley Nicole Black.

These women are doing heroic work. And still, it’s hard not to wonder what might be achievable if powerful men — athletes, team owners, legions of fans — could set aside their “precarious manhood,” to use the academic term of art.

“We have to pull in everybody,” Hershkowitz said.

Mookie Betts probably isn’t going to start posting to Instagram about voting climate deniers out of office, or gabbing on his podcast about ending fossil fuel sponsorships. (Although either would be good!) But he does have a great charitable foundation that focuses on physical fitness, mental health, nutrition and financial literacy for young people. It would be easy to fit a climate initiative into those buckets, and for Mookie to spread the word. Other male athletes could take similar approaches.

Some fans would get annoyed. More would listen. They’d learn that there’s nothing feminine about caring for the climate.

Not that it should matter. But it does.

News on Phillips 66 and the Dodgers

Houston-based oil company Phillips 66, whose 76 gasoline brand has advertised at Dodger Stadium since the 1960s, was scheduled to stand trial next month on several counts of violating the Clean Water Act by dumping industrial wastewater into the L.A. County sewer system at its oil refinery in Carson.

Now the trial may not happen.

In a December 26 legal filing, the company informed the federal judge assigned to the case that the parties — aka Phillips 66 and the Trump administration’s Department of Justice — “have reached an agreement to settle this matter.” The parties were working out the details and expected to finalize the settlement by January 16, aka today.

Given the pending settlement, the judge paused pre-trial proceedings. As of yesterday afternoon, the settlement still hadn’t been filed.

Even so, the activists urging the Dodgers to dump Phillips 66 are forging ahead with plans for a protest on February 17, when the trial would have taken place. Instead of the courthouse, they’ll be outside Dodger Stadium — and at up to 10 other baseball, football, basketball and soccer fields across the U.S., all home to teams with sponsors from the fossil fuel industry (or oily banks or fossil-heavy utilities).

Zan Dubin, the lead organizer for Dodger Fans Against Fossil Fuels, said the group is recruiting activists for the other stadiums.

“We are ready to make noise in a peaceful way,” she said in an email.

In other news

Apologies in advance…we’re starting with some gloomy stories today.

Less-than-hopeful trends:

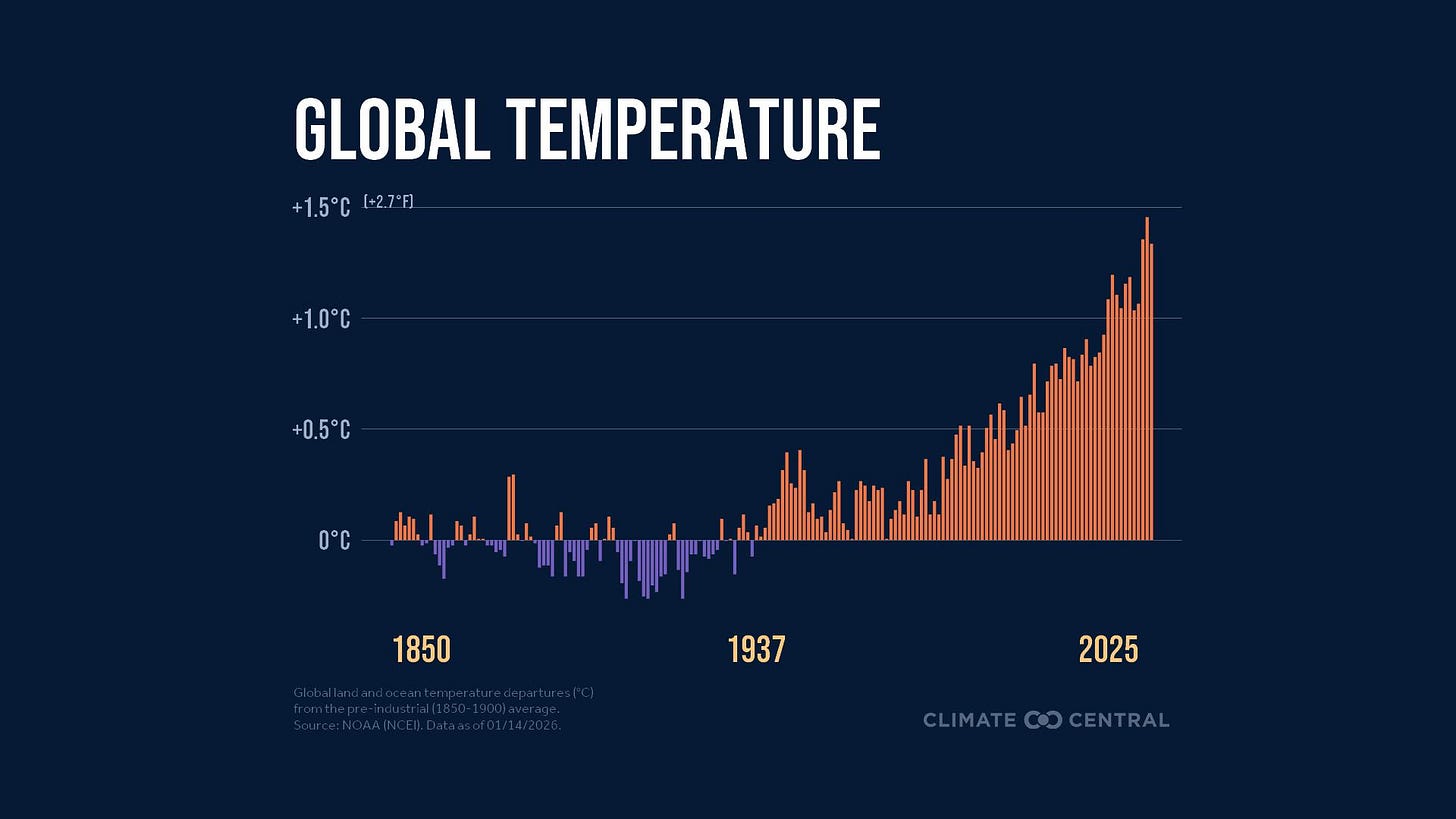

2025 was Earth’s third-hottest year on record. (Ajit Niranjan and Oliver Milman, the Guardian)

U.S. carbon emissions rose last year, as rising electric demand and high gas prices caused coal plants to operate longer hours. (Julian Spector, Canary Media)

Despite worsening weather extremes, “the climate reporting of the 2020s feels somehow less insistent and pressing than that of 10 years ago. The warning-bell coverage has morphed into the hum of beat reporting as the impacts of climate chaos pile up.” (Jason Dove Mark, Earth Island Journal)

Latest Trump stuff:

Trump pulled the U.S. out of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, making America the only country that’s not a member. This is like leaving the Paris Agreement but even dumber. (Hayley Smith, L.A. Times)

Trump’s EPA will stop considering lives saved from reducing air pollution, and only consider costs to industry. Which raises the question, what’s the point of an Environmental Protection Agency? (Maxine Joselow, New York Times)

Careful if you put a sticker over Trump’s face on your national parks pass. You might have to pay for a new pass. (Sam Hill, SFGATE)

Actual good news:

California’s Westlands Water District approved a plan to build solar and battery storage across up to 136,000 acres of San Joaquin Valley farmland. The land could meet a quarter of the state’s clean energy needs. (Jeff St. John, Canary Media)

California is totally drought-free for the first time in 25 years. Most reservoirs are in good shape and wildfire risk is low. (Clara Harter, L.A. Times)

Gavin Newsom’s budget proposal includes $200 million in new incentives for electric vehicle sales, to help make up for Trump and congressional Republicans canceling federal EV tax credits. (Hayley Smith, L.A. Times)

Water in the West:

Federal officials are ramping up pressure on Colorado River states to strike a deal to avert “dead pool” at Lake Mead and Lake Powell. (Ian James, L.A. Times)

The Trump administration is trying to block a dam removal that would make the Eel River the Golden State’s longest free-flowing waterway. (Kurtis Alexander, San Francisco Chronicle)

Arizona is cracking down on groundwater pumping in a valley where the largest water user is a Saudi-owned dairy company. (Ian James, L.A. Times)

Finally, The Times’ Susanne Rust reports that the Newsom administration has once again delayed landmark single-use plastic regulations. Susanne has covered this story doggedly, even in the face of bizarre threats from Newsom’s office. Go Susanne.

Best comment I've heard yet about this column/study: Guys, get a clue, climate protests are where you meet girls :)

The fact that men are less likely to be concerned about climate change isn't exactly surprising, but I think it's something all of us in the climate movement are going to have to figure out how to address. I've made the point to several friends and colleagues that we need more examples of male leadership on climate issues -- not just in business or politics, but in pop culture.

Where are the action heroes driving an EV in a high-stakes chase scene? Or the male athletes refusing to play for a team that accepts fossil fuel money? Or the A-list male celebrity extolling the virtues of a vegan diet?

There are isolated examples if you know where to look, but countering cultural stereotypes is going to take concerted and coordinated action. Maybe we can start by making the next F1 movie about how cool and fast EVs are now. Or turn the Avengers into climate heroes. Or come up with a romcom where the male lead only gets the girl after coming up with a way to save the planet. Audiences are so hungry for this kind of entertainment.