Climate change goes to the theater

A high school musical, and a time-travel play inspired by "Frankenstein," show that anything can make a great climate story.

A depressed middle-aged man finds himself transported back to high school, where the same old bullies torment him for being a gay theater nerd — only this time, he’s ready to fight back. With help from Frankenstein’s monster.

A 16-year-old Hispanic girl, long scorned by her upper-class white classmates, goes viral on social media. Suddenly all the popular kids — the ones whose families belong to the country club where she works — want to be her friend.

Two creative and compelling narratives, both performed on stage. Neither necessarily needing a climate change angle.

But both far better for meeting audiences where we’re at: living in a world defined by rising temperatures, and consumed by a burning desire to act.

So let’s talk climate theater, starting with the first play I mentioned above, the one with time travel and high school bullying. It’s called “The Year We Disappeared,” and I caught a showing last month at Anthony Meindl’s Actor Workshop in Hollywood.

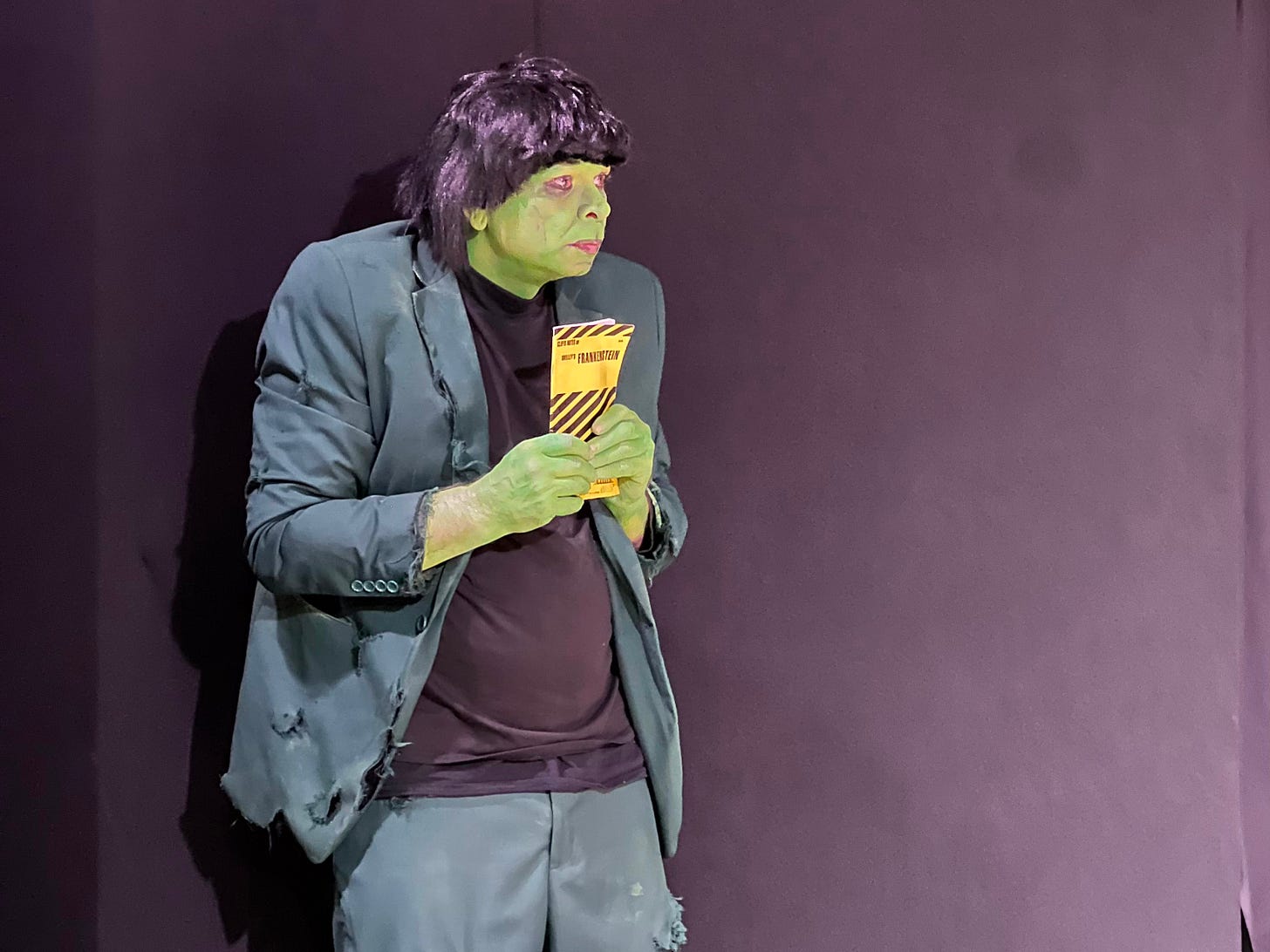

Written and directed by Meindl — and based loosely on his own experience growing up closeted in Indiana, he told me — it’s a fever dream of a production, with a surreal story grounded by powerful emotional beats. The teenage protagonist, Joseph, finds himself turning into Frankenstein’s monster, green skin and all, as he becomes a bully himself. “Frankenstein” author Mary Shelley makes an exhilarating appearance during a time-travel sequence to the early 1800s.

The climate themes build slowly, with hints of extreme weather in the present and references to climate scientist James Hansen’s famous 1988 Senate testimony in the past. During a school trip to Washington, D.C., Joseph ultimately bumps into Hansen. Their conversation helps him overcome his own trauma — and figure out why science will never defeat Big Oil with facts alone. Feelings are just as important.

“The real purpose of art is to help bring awareness of who we are as human beings, as spiritual beings,” Meindl said. “And the only way we can do that is to reflect back the parts of ourselves — the parts of society — that we’re scared to look at.”

That may sound abstract. But really all it means is that art — films, TV shows, plays, etc. — help us deal with difficult topics. By threading a climate angle through a story about a teenager hellbent on revenge, Meindl helps theatergoers process the climate disasters that increasingly surround them (i.e. the Los Angeles wildfires).

“The real science fiction is pretending it isn’t happening,” he said.

The second play tackles the climate crisis even more directly.

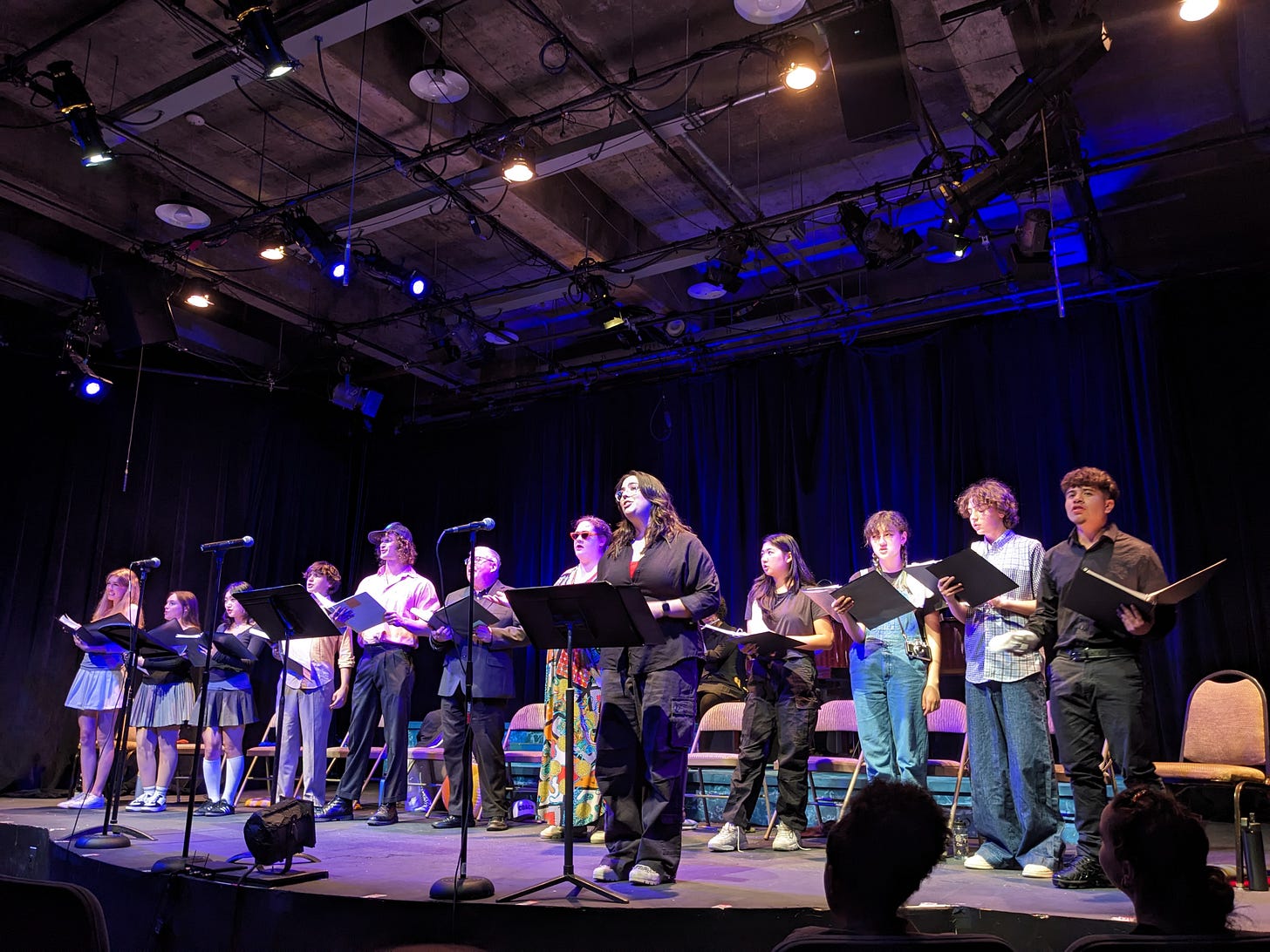

It’s a musical called “350 parts per million,” and sadly it’s only been performed once, a staged reading in San Francisco. I wasn’t there, but the soundtrack is online, and it’s delightful. It was written and composed by Marisa Mitchell, who also sent me a copy of her script. She’s a renewable energy executive who somehow taught herself to make a musical.

“In Covid, I decided that I was probably ripe for a midlife crisis. And rather than have a midlife crisis, I made a list of all of the things that brought me joy and made me feel like I had a meaningful job to do in the world,” she told me. “And the Venn diagram of that was basically that I should write a musical about the climate crisis.”

The result is 16-year-old Cora Mariposa, who came to the U.S. as a child and wants to be a climate scientist. “350 parts per million” refers to a long-since-exceeded, science-based target to limit atmospheric carbon dioxide levels.

But although climate is central to the plot, some of the most moving scenes deal with immigration, race and class. I also identified with the teenage characters struggling to navigate the often-toxic role of social media in their lives.

And while Cora ultimately goes viral after confronting an oil company stooge — an incident that launches her on the path to activism — she could have been written as a foil to some other destructive industry. The climate angle improves the story, but the characters and their relationships are compelling on their own.

Fortunately, Mitchell wanted to tell a climate story — specifically a story that left audiences feeling empowered. Unlike, say, Adam McKay’s “Don’t Look Up,” which ends with the climate-metaphor comet obliterating Earth.

“As I was looking at other stories that were trying to convey things about the climate crisis, they were missing the ‘what the hell do we do about it’ piece,’” she said. “They were either apocalyptic or [unduly] hopeful.”

Indeed, global warming is complicated. It’s not the apocalypse, but it won’t be easy to solve either, even with all the technological tools at our disposal.

That’s a hard enough story for a scientist or journalist to tell, let alone a playwright or screenwriter. There’s a reason few movies or TV shows mention climate change, and fewer still go beyond misleading end-of-world tropes.

So it’s encouraging to see artists using local theater to experiment — and succeeding. Here we have a high school musical and a time-travel phantasmagoria showing that anything can make a good climate story.

Now wouldn’t it be great if some production companies or grant funders could help these folks refine their visions and bring their stories to more people?

“I feel like it’s got so much potential,” Meindl said, referring to his play. “If you know a rich sugar daddy…”

You never know where hits will come from. “Frankenstein” exists because a volcanic eruption sent dark rain clouds sweeping over Europe in 1816, inspiring an 18-year-old Shelley, her lover and their friends to write spooky stories.

To Meindl, “Frankenstein” is the world’s first work of “cli-fi,” or climate fiction, even if Shelley wouldn’t have called it that.

“There were crop failures. The first recorded climate refugees. People were dying,” he said. “She wrote ‘Frankenstein’ as a response to all these climatic events.”

Just six years after the book’s publication, physicist Joseph Fourier first proposed the greenhouse effect — the idea that certain gases might trap heat in the atmosphere.

He was right. Two centuries later, we have crop failures, climate refugees and people dying — and artists, once again, responding.

Wish I could've seen either of these plays! I never even made the Frankenstein connection. Will be interesting to see if the new one out on Netflix touches on any climate themes.

Thank you for bringing accessible climate stories to our attention. Climate Conversations is taking note.